Many companies have some version of Training Stress Score (TSS). It’s supposed to represent how hard a training session is and the chronic accumulation of training stress is supposedly representative of your fitness. It is a system employed in all training analytics software built for cyclists or endurance athletes in some way or another. Here we are going to talk through TSS and explain how to calculate it, the sort of values you should be aiming for (if any) as well as some alternative ways of measuring training load. The short version is that TSS is a useful metric to have in a wider context of your training week, month and season but it’s not the be all and end all – at the end of the day these measures are just numbers made up by software developers (like me) and are useful as a proxy measure to model your fitness at some given time but they’re not perfect, often wrong and worth something only in context.

What is TSS and how is it calculated

In this example I will talk through the version of TSS employed by Training Peaks – this is because it’s the method I’m most familiar with as a Training Peaks user myself. Other brands including Strava, Garmin, Wahoo and Today’s Plan (and many more) use a similar but slightly different model for calculating TSS. This is why you might notice differences between Strava, Wahoo and Training Peaks when you upload your ride, for example. For simplicity we will also stick to cycling – TSS for running and swimming are calculated in a similar way.

Many cyclists are familiar with the term FTP (Functional Threshold Power) and it’s broadly understood by cyclists to be the effort that you can sustain for an hour. TSS is calculated using this number too. Imagine, for example, your FTP is 400 Watts (I often imagine my FTP is this big). If you go and ride at 400W exactly for an hour then you will have a TSS for that ride of 100. The TSS of any ride is proportional to the ratio of your normalised power to your threshold power multiplied by your ride time. The exact coefficient depends on the method used to calculate TSS (or equivalent) but they usually work off the basis that 100TSS in 60 minutes is a maximal effort.

Is more always better?

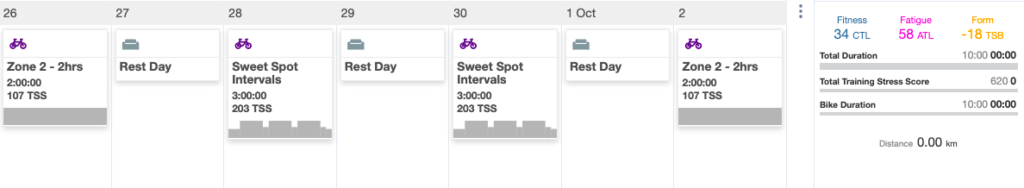

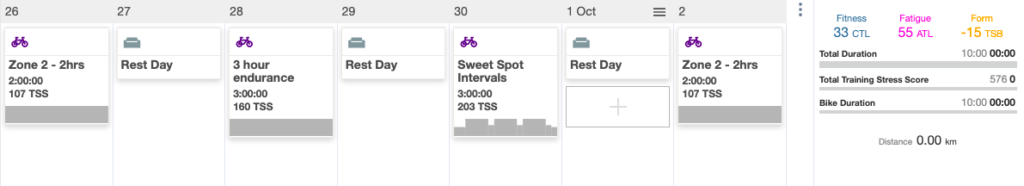

Now we know how to calculate TSS we come to the question of “What should I be aiming for?”. The answer is simple – as much as is sustainable. Training causes a stress on our body, adaptation to that stress makes us fitter. Repeat that process a million times and you get a lot faster – it’s very simple. However, this is where the limitations of training stress as a measure of load come in. Consider the following two training weeks by a rider with 10 hours to train…

The above week contains two hard interval sessions and 620TSS, the below week contains one hard session and 576TSS.

We know that success in endurance sport is often achieved by using intensity sparingly in our training, so even though an athlete in the top week would be “fitter” the athlete in week 2 is training “more effectively” (according to the literature). This means that more is not always better and that intensity distribution as well as total load should be considered when evaluating the potential of a training programme for us to achieve our goals. TSS does not allow us to assess the sustainability in our training. There is only a 7% difference in TSS in these examples however the training week in the top example is significantly less sustainable and much harder.

Pros and cons of using TSS to measure load

TSS is good because it’s a simple metric which allows you to judge a training session’s difficulty – this means you can also plan training around a big ride a little more easily. The downside is that it doesn’t take into account a session’s length nor does it take into account a session’s position in the training week. For example – a 2 hour endurance ride is harder if you’ve done intervals the day before yet the TSS will be the same however the training stimulus is not. This is the same the other way around too. If you are training for a bike race when the big moves happen at the end you’ll likely want to do a session that reflects this. Consider a session with 4 x 5 minute intervals at the end of a 2 hour ride and another at the start of a 2 hour ride. Anyone who’s ever done this will tell you that doing these intervals at the end of the 2 hour effort is much harder (and as a result places a greater stress on the body). Yet, when we check their TSS we find that the value is the same. This is a clear limitation of using this method as a means of measuring load.

Alternative ways to measure our training

The alternative to this is hours – hours of easy and hours of “hard”. Of course, defining “hard” varies from person to person but I would define “hard” as anything above zone two – or anything harder than your first lactate threshold. For our rider with an FTP of 400W this would mean roughly any riding over 300W. The downside of this method is similar to the downside of TSS – it doesn’t reflect that training under load is a greater stress however it does work better in the context of a training week. For example, accumulating 18 hours of aerobic training and 1 hour of training above LT1 is a more useful thing to know than some value of TSS.

TSS is a useful metric, no doubt. It gives us a quick reference point for how hard a ride has been and is one way to measure load. However, it’s also not perfect and should be taken with a pinch of salt. I find it best to keep training simple, accumulate as much aerobic volume as possible and include a sprinkling of intensity – no more than 20% of your total volume.

Check out bespoke home insurance just for cyclists here with Pedal Cover!